Capitalizing on tiny defects can improve electrodes for lithium-ion batteries, new research suggests.

Capitalizing on tiny defects can improve electrodes for lithium-ion batteries, new research suggests.

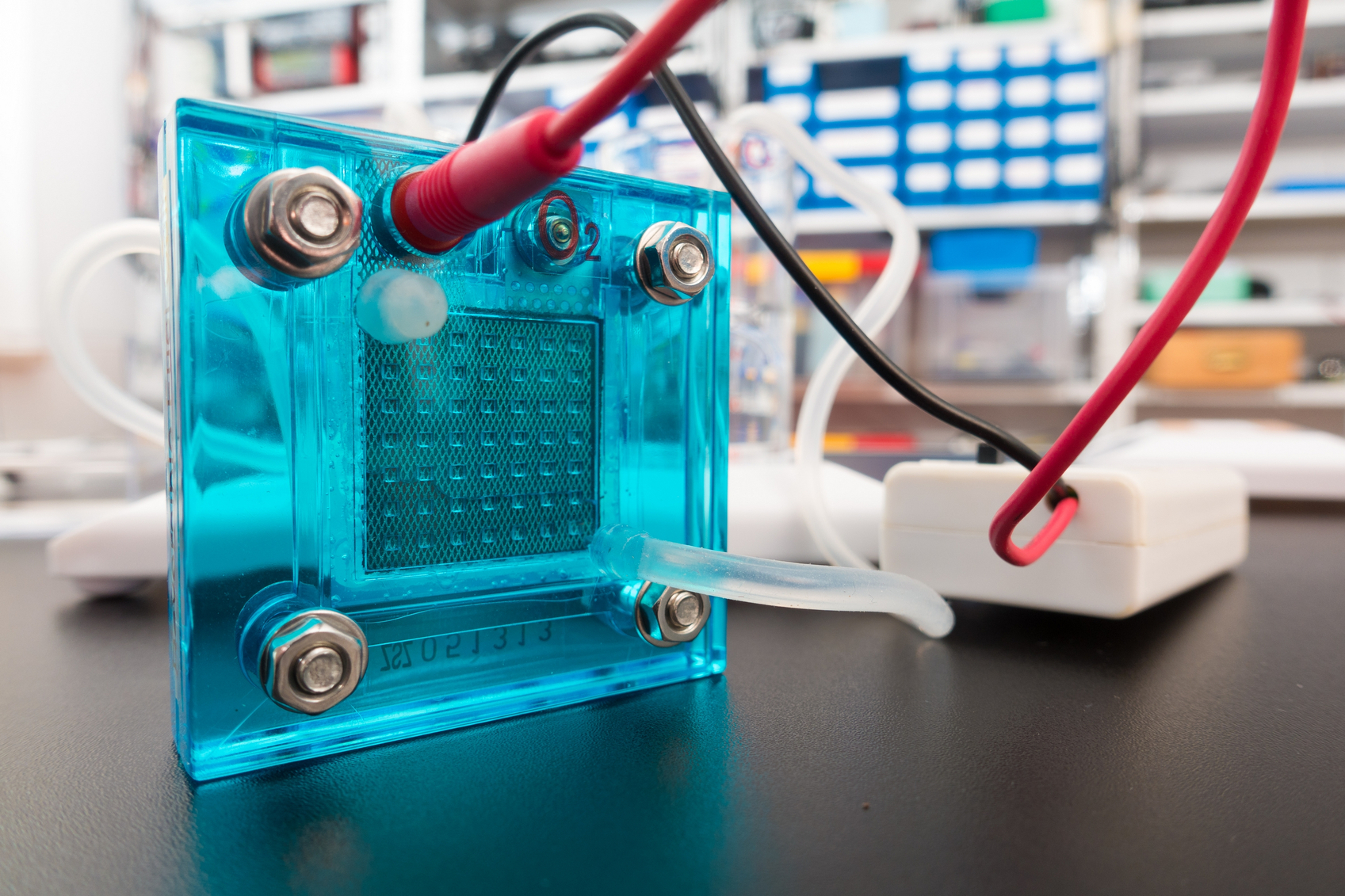

In a study on lithium transport in battery cathodes, researchers found that a common cathode material for lithium-ion batteries, olivine lithium iron phosphate, releases or takes in lithium ions through a much larger surface area than previously thought.

“We know this material works very well but there’s still much debate about why,” says Ming Tang, an assistant professor of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice University. “In many aspects, this material isn’t supposed to be so good, but somehow it exceeds people’s expectations.”

Part of the reason, Tang says, comes from point defects—atoms misplaced in the crystal lattice—known as antisite defects. Such defects are impossible to completely eliminate in the fabrication process. As it turns out, he says, they make real-world electrode materials behave very differently from perfect crystals.

A new sodium-based battery can store the same amount of energy as a state-of-the-art lithium ion at a substantially lower cost.

A new sodium-based battery can store the same amount of energy as a state-of-the-art lithium ion at a substantially lower cost. A closer look at catalysts is giving researchers a better sense of how these atom-thick materials produce hydrogen.

A closer look at catalysts is giving researchers a better sense of how these atom-thick materials produce hydrogen. Engineers working to make solar cells more cost effective ended up finding a method for making sonar-like collision avoidance systems in self-driving cars.

Engineers working to make solar cells more cost effective ended up finding a method for making sonar-like collision avoidance systems in self-driving cars. Just a few months ago, business magnate Elon Musk announced that he would spearhead an effort to build the

Just a few months ago, business magnate Elon Musk announced that he would spearhead an effort to build the  Lithium batteries made with asphalt could charge 10 to 20 times faster than the commercial lithium-ion batteries currently available.

Lithium batteries made with asphalt could charge 10 to 20 times faster than the commercial lithium-ion batteries currently available.