Safety concerns regarding lithium-ion batteries have been making headlines in light of smartphone fires and hoverboard explosions. In order to combat safety issues, at team of researchers from Drexel University, led by ECS member Yury Gogotsi, has developed a way to transform a battery’s electrolyte solution into a safeguard against the chemical process that leads to battery fires.

Safety concerns regarding lithium-ion batteries have been making headlines in light of smartphone fires and hoverboard explosions. In order to combat safety issues, at team of researchers from Drexel University, led by ECS member Yury Gogotsi, has developed a way to transform a battery’s electrolyte solution into a safeguard against the chemical process that leads to battery fires.

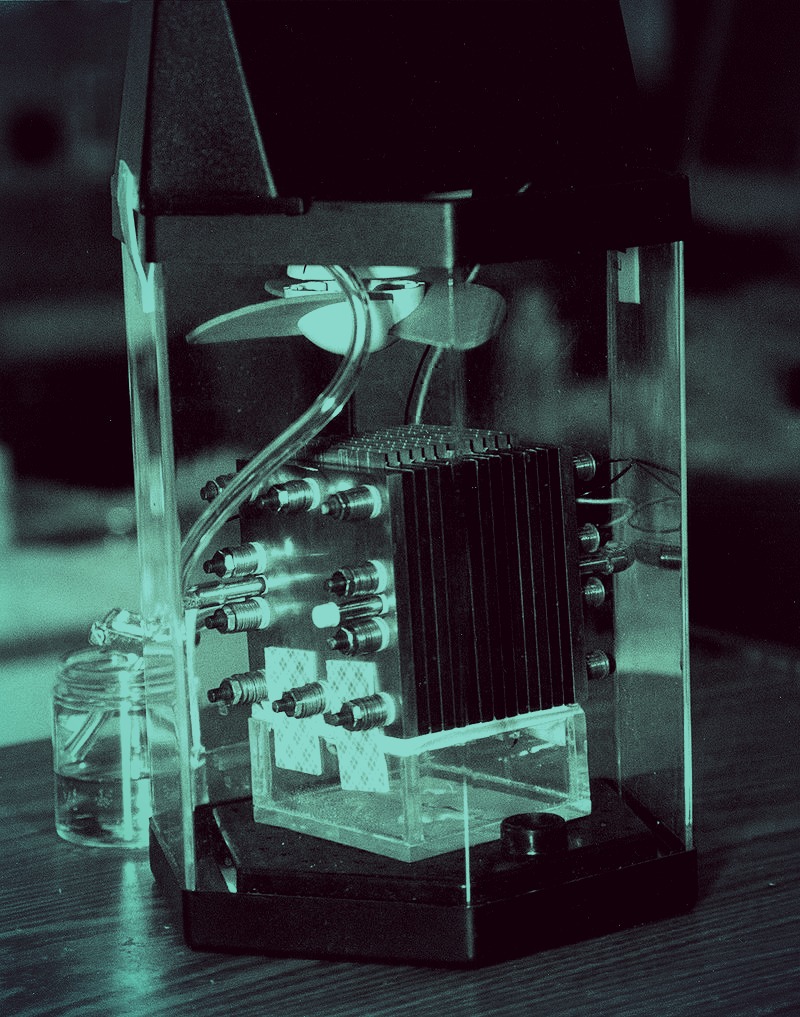

Dendrites – or battery buildups caused by the chemical reactions inside the battery – have been cited as one of the main causes of lithium-ion battery malfunction. As more dendrites compile over time, they can breach the battery’s separator, resulting in malfunction.

(MORE: Read more research by Gogotsi in the ECS Digital Library.)

As part of their solution to this problem, the research team is using nanodiamonds to curtail the electrochemical deposition that leads to the short-circuiting of lithium-ion batteries. To put it in perspective, nanodiamond particles are roughly 10,000 times smaller than the diameter of a single hair.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)  Researchers have created a new method to more efficiently convert potato waste into ethanol. The findings may lead to reduced production costs for biofuel in the future and add extra value for chip makers.

Researchers have created a new method to more efficiently convert potato waste into ethanol. The findings may lead to reduced production costs for biofuel in the future and add extra value for chip makers.

While pursing work on the highly desirable but technically challenging lithium-air battery, researchers unexpectedly discovered a new way to capture and store carbon dioxide. Upon creating a design for a lithium-CO2 battery, the research team found a way to isolate solid carbon dust from gaseous carbon dioxide, all while being able to separate oxygen.

While pursing work on the highly desirable but technically challenging lithium-air battery, researchers unexpectedly discovered a new way to capture and store carbon dioxide. Upon creating a design for a lithium-CO2 battery, the research team found a way to isolate solid carbon dust from gaseous carbon dioxide, all while being able to separate oxygen. This summer I worked on the Greenland ice sheet, part of a scientific experiment to study surface melting and its contribution to Greenland’s accelerating ice losses. By virtue of its size, elevation and currently frozen state, Greenland has the potential to cause large and rapid increases to sea level as it melts.

This summer I worked on the Greenland ice sheet, part of a scientific experiment to study surface melting and its contribution to Greenland’s accelerating ice losses. By virtue of its size, elevation and currently frozen state, Greenland has the potential to cause large and rapid increases to sea level as it melts. Researchers have found a new method for finding lithium, used in the lithium-ion batteries that power modern electronics, in supervolcanic lake deposits.

Researchers have found a new method for finding lithium, used in the lithium-ion batteries that power modern electronics, in supervolcanic lake deposits.