Using energy stored in the batteries of electric vehicles to power large buildings not only provides electricity for the building, but also increases the lifespan of the vehicle batteries, new research shows.

Using energy stored in the batteries of electric vehicles to power large buildings not only provides electricity for the building, but also increases the lifespan of the vehicle batteries, new research shows.

Researchers have demonstrated that vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology can take enough energy from idle electric vehicle (EV) batteries to be pumped into the grid and power buildings—without damaging the batteries.

This new research into the potentials of V2G shows that it could actually improve vehicle battery life by around ten percent over a year.

For two years, Kotub Uddin, a senior research fellow at the University of Warwick’s Warwick Manufacturing Group, and his team analyzed some of the world’s most advanced lithium ion batteries used in commercially available EVs—and created one of the most accurate battery degradation models existing in the public domain—to predict battery capacity and power fade over time, under various aging acceleration factors—including temperature, state of charge, current, and depth of discharge.

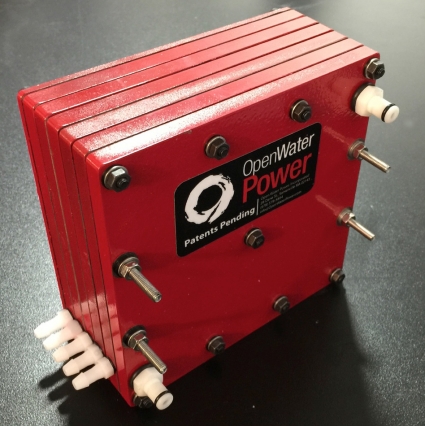

A new development in electrolyte chemistry, led by ECS member

A new development in electrolyte chemistry, led by ECS member  Researchers have developed a new kind of semiconductor alloy capable of capturing the near-infrared light located on the edge of the visible light spectrum.

Researchers have developed a new kind of semiconductor alloy capable of capturing the near-infrared light located on the edge of the visible light spectrum.

A new study describes the mechanics behind an early key step in artificially activating carbon dioxide so that it can rearrange itself to become the liquid fuel ethanol.

A new study describes the mechanics behind an early key step in artificially activating carbon dioxide so that it can rearrange itself to become the liquid fuel ethanol. In an effort to increase security on airplanes, the U.S. government is considering expanding a ban on lithium-ion based devices from cabins of commercial flights, opting instead for passengers to transport laptops and other electronic devices in their checked luggage in the cargo department. However, statistics from the Federal Aviation Administration suggest that storing those devices in the cargo area

In an effort to increase security on airplanes, the U.S. government is considering expanding a ban on lithium-ion based devices from cabins of commercial flights, opting instead for passengers to transport laptops and other electronic devices in their checked luggage in the cargo department. However, statistics from the Federal Aviation Administration suggest that storing those devices in the cargo area  Assuming that the deployment of carbon removal technology will outpace emissions and conquer global climate change is a poor substitute for taking action now, say researchers.

Assuming that the deployment of carbon removal technology will outpace emissions and conquer global climate change is a poor substitute for taking action now, say researchers. In its first “

In its first “ In 2016,

In 2016,