Assuming that the deployment of carbon removal technology will outpace emissions and conquer global climate change is a poor substitute for taking action now, say researchers.

Assuming that the deployment of carbon removal technology will outpace emissions and conquer global climate change is a poor substitute for taking action now, say researchers.

With the current pace of renewable energy deployment and emissions reductions efforts, the world is unlikely to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This trend puts in doubt efforts to keep climate change damages from sea level rise, heat waves, drought, and flooding in check. Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, also known as “negative emissions,” has been thought of as a potential method of fighting climate change.

In their new perspective published in the journal Science, however, researchers from Stanford University explain the risks of assuming carbon removal technologies can be deployed at a massive scale relatively quickly with low costs and limited side effects—with the future of the planet at stake.

“For any temperature limit, we’ve got a finite budget of how much heat-trapping gases we can put into the atmosphere. Relying on big future deployments of carbon removal technologies is like eating lots of dessert today, with great hopes for liposuction tomorrow,” says Chris Field, professor of biology and of earth system science and director of Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

In its first “

In its first “ In 2016,

In 2016,  The U.S. Department of Energy spends

The U.S. Department of Energy spends  The

The  U.S. Secretary of Energy Rick Perry in April

U.S. Secretary of Energy Rick Perry in April  The consumer demand for seamless, integrated technology is on the rise, and with it grows the Internet of Things, which is expected to grow to a

The consumer demand for seamless, integrated technology is on the rise, and with it grows the Internet of Things, which is expected to grow to a  Lithium-ion batteries power a vast majority of the world’s portable electronics, but the magnification of recent safety incidents have some looking for new ways to keep battery-related hazards at bay. The U.S. Navy is one of those groups, with chemists in the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) unveiling a new battery, which they say is both safe and rechargeable for applications such as electric vehicles and ships.

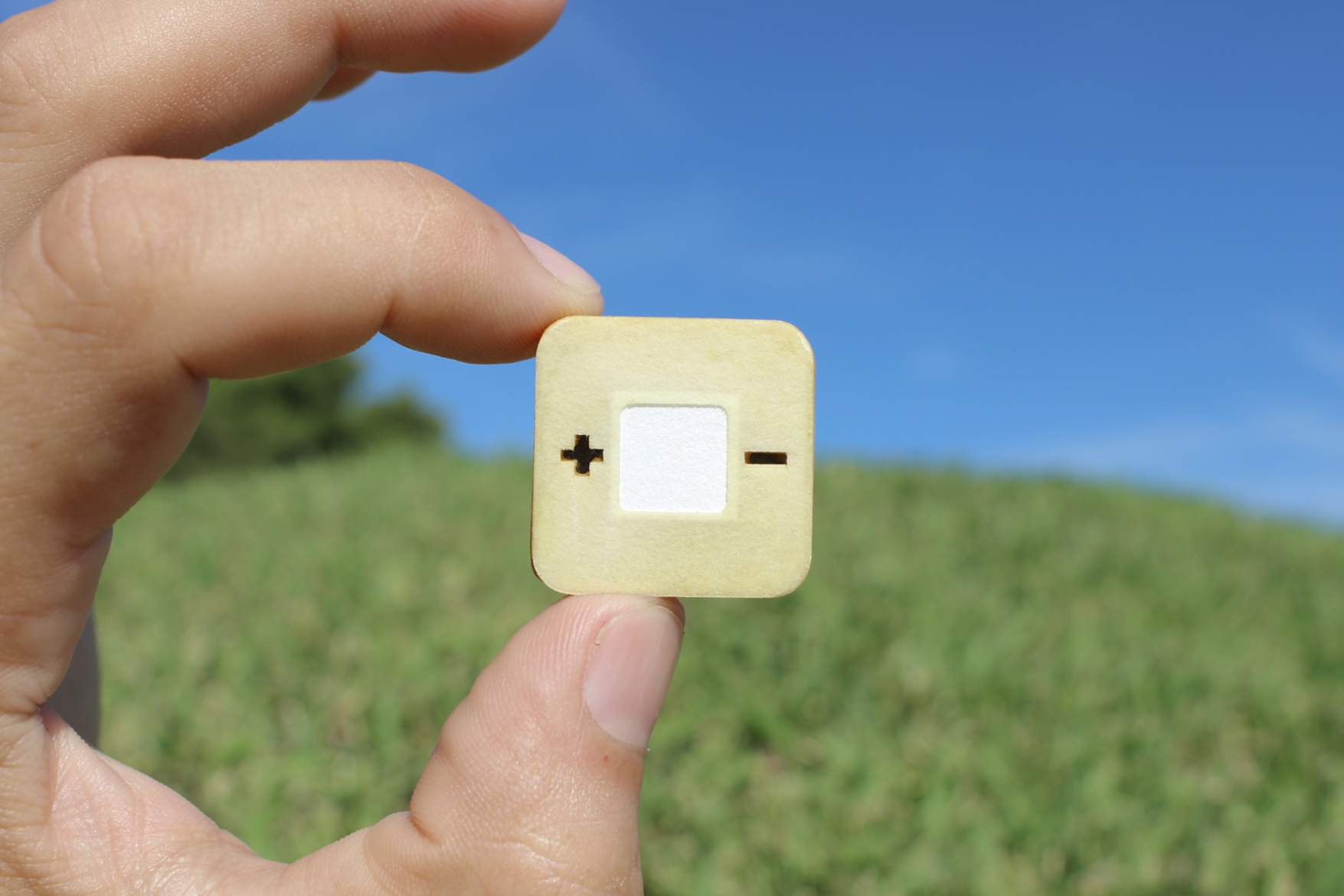

Lithium-ion batteries power a vast majority of the world’s portable electronics, but the magnification of recent safety incidents have some looking for new ways to keep battery-related hazards at bay. The U.S. Navy is one of those groups, with chemists in the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) unveiling a new battery, which they say is both safe and rechargeable for applications such as electric vehicles and ships. Like all things, batteries have a finite lifespan. As batteries get older and efficiency decreases, they enter what researchers call “capacity fade,” which occurs when the amount of charge your battery could once hold begins to decrease with repeated use.

Like all things, batteries have a finite lifespan. As batteries get older and efficiency decreases, they enter what researchers call “capacity fade,” which occurs when the amount of charge your battery could once hold begins to decrease with repeated use.