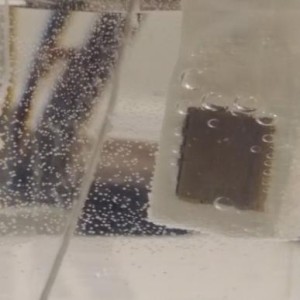

Water splitting into hydrogen on a metal wire and oxygen on the catalyst.

Source: Yale Entrepreneurial Institute

New research out of Yale University, led by Ph.D. student Staff Sheehan, recently unveiled a new catalyst to aid in the generation of renewable fuels.

Sheehan’s main area of research has been water splitting. In his recently published paper, he takes the theories and processes involved in water splitting and uses a specific iridium species as a water oxidation catalyst. This has led to new breakthroughs in artificial photosynthesis to develop renewable fuels.

“Artificial photosynthesis has been widely researched,” Sheehan says, “but water oxidation is the bottleneck—it’s usually the most difficult reaction to perform in generating fuel from sunlight.”