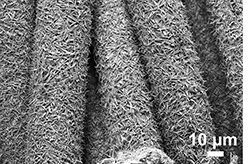

Nanostructures on the surface of the fabric.

Image: Queensland University of Technology

Oil spills have had an extensive history of disrupting the environment, killing ecosystems, and displacing families. Impacts of massive oil spills are still felt in many parts of the world, including the undersea spill at the BP oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico that dumped an approximate 39 million gallons of oil into the gulf.

But what if these devastating oil spills could be easily cleaned up with a piece of fabric rooted in electrochemistry?

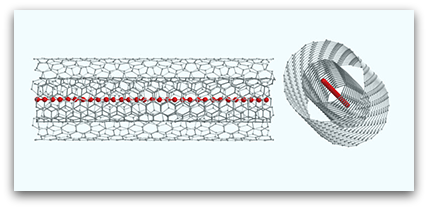

That may be a reality soon thanks to researchers at Queensland University of Technology (QUT). According to a release, the QUT researchers have developed a multipurpose fabric covered with semi-conducting nanostructures that can both mop up oil and degrade organic matter when exposed to light.

The fabric, which repels water and attracts oil, has already has promising preliminary results. In the early stages of research, the scientists have already been able to mop up crude oil from the surface of both fresh and salt water.

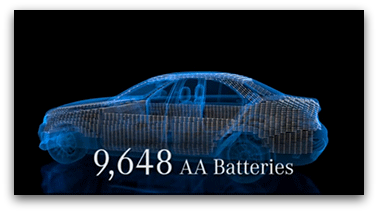

There may soon be a shift in the transportation sector, where traditional fossil fuel-powered vehicles become a thing of the past and electric vehicles start on their rise to dominance.

There may soon be a shift in the transportation sector, where traditional fossil fuel-powered vehicles become a thing of the past and electric vehicles start on their rise to dominance. Globally, open access can help create a world where everyone from the student in Atlanta to a researcher in Haiti can freely read the scientific papers they need to make a discovery; where scientific breakthroughs in energy conversion, sensors, or nanotechnology are unimpeded by fees to access or publish research.

Globally, open access can help create a world where everyone from the student in Atlanta to a researcher in Haiti can freely read the scientific papers they need to make a discovery; where scientific breakthroughs in energy conversion, sensors, or nanotechnology are unimpeded by fees to access or publish research.