By: Peter Byrley, University of California, Riverside

Image: CC0 Public Domain

A smartphone touchscreen is an impressive piece of technology. It displays information and responds to a user’s touch. But as many people know, it’s easy to break key elements of the transparent, electrically conductive layers that make up even the sturdiest rigid touchscreen. If flexible smartphones, e-paper and a new generation of smart watches are to succeed, they can’t use existing touchscreen technology.

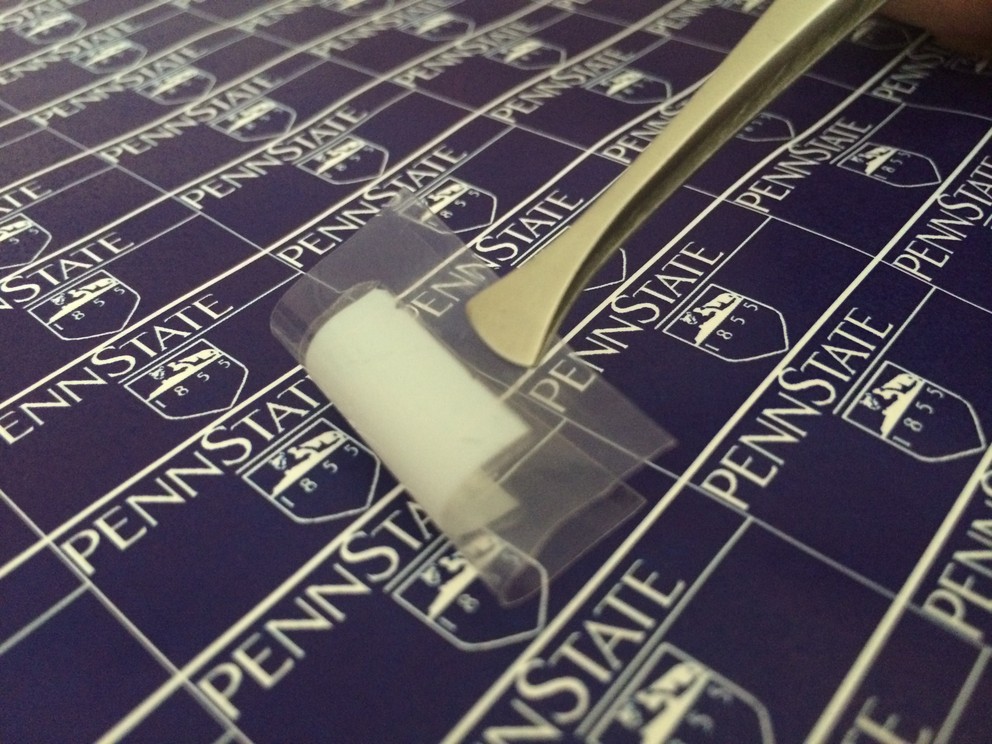

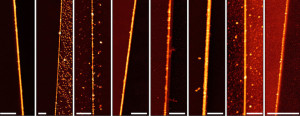

We’ll need to invent something new – something flexible and durable, in addition to being clear, lightweight, electrically responsive and inexpensive. Many researchers are pursuing potential options. As a graduate researcher at the University of California, Riverside, I’m part of a research group working to solve this challenge by weaving mesh layers out of microscopic strands of metal – building what we call metal nanowire networks.

These could form key components of new display systems; they could also make existing smartphones’ touchscreens even faster and easier to use.

The problem with indium tin oxide

A standard smartphone touchscreen has glass on the outside, on top of two layers of conductive material called indium tin oxide. These layers are very thin, transparent to light and conduct small amounts of electrical current. The display lies underneath.

When a person touches the screen, the pressure of their finger bends the glass very slightly, pushing the two layers of indium tin oxide closer together. In resistive touchscreens, that changes the electrical resistance of the layers; in capacitive touchscreens, the pressure creates an electrical circuit.