Researchers from MIT have developed a new way to extract copper by separating the commercially valuable metal from sulfide minerals in one step without harmful byproducts. The goal of this new process is to simplify metal production, thereby eliminating harmful byproducts and driving down costs.

Researchers from MIT have developed a new way to extract copper by separating the commercially valuable metal from sulfide minerals in one step without harmful byproducts. The goal of this new process is to simplify metal production, thereby eliminating harmful byproducts and driving down costs.

To achieve this result, the team used a process called molten electrolysis. Electrolysis is a common technique used to break apart compounds, often seen in water splitting to separate hydrogen from oxygen. The same process is also used in aluminum production and as a final step in copper production to remove any impurities. However, electrolysis in copper production is a multistep process that emits sulfur dioxide.

This from MIT:

Contrary to aluminum, however, there are no direct electrolytic decomposition processes for copper-containing sulfide minerals to produce liquid copper.

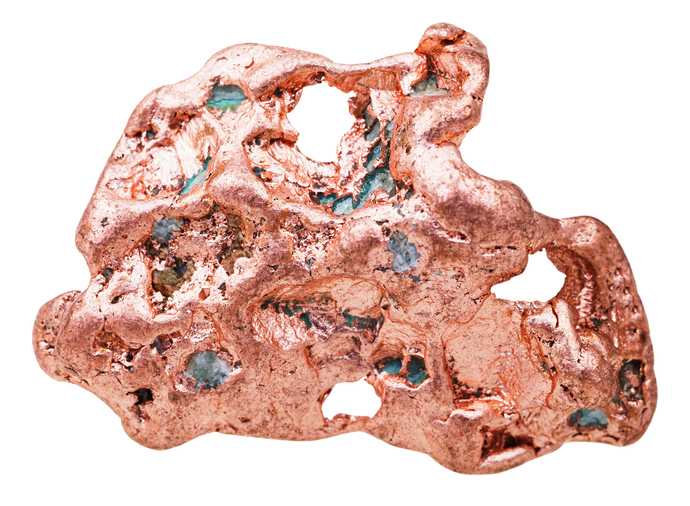

The MIT researchers found a promising method of forming liquid copper metal and sulfur gas in their cell from an electrolyte composed of barium sulfide, lanthanum sulfide, and copper sulfide, which yields greater than 99.9 percent pure copper. This purity is equivalent to the best current copper production methods. Their results are published in an Electrochimica Acta paper with senior author Antoine Allanore, assistant professor of metallurgy.

“It is a one-step process, directly just decompose the sulfide to copper and sulfur. Other previous methods are multiple steps,” says Sulata K. Sahu, postdoc at MIT and co-author of the recently published paper. “By adopting this process, we are aiming to reduce the cost.”

Driving down the cost of copper could play a critical role in the production of such items as electric vehicles, solar energy, and consumer electronics.

The new work builds on a 2016 paper published in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society. The initial paper, also co-authored by ECS member Allanore, offered proof of the electrolytic extraction of copper.

(READ: Electrochemistry of Molten Sulfides: Copper Extraction from BaS-Cu2S)

“This paper was the first one to show that you can use a mixture where presumably electronic conductivity dominates conduction, but there is not actually 100 percent. There is a tiny fraction that is ionic, which is good enough to make copper,” Allanore says. “The new paper shows that we can go further than that and almost make it fully ionic, that is reduce the share of electronic conductivity and therefore increase the efficiency to make metal.”