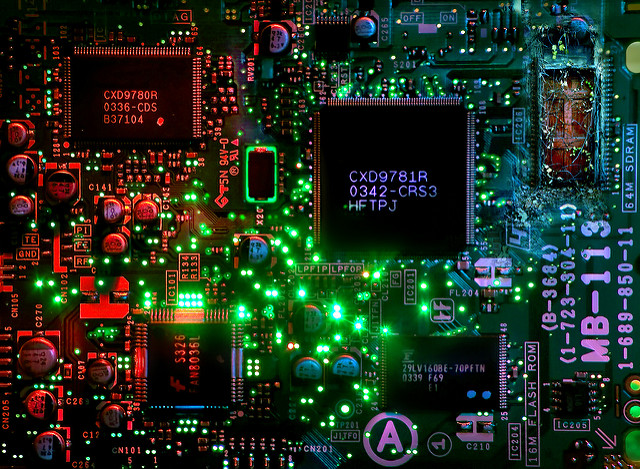

The future of technology

Image: Tau Zero/Flickr

The iconic Moore’s law has guided Silicon Valley and the technology industry at large for over 50 years. Moore’s prediction that the number of transistors on a chip would double every two years (which he first articulated at an ECS meeting in 1964) bolstered businesses and the economy, as well as took society away from the giant mainframes of the 1960s to today’s era of portable electronics.

But research has begun to plateau and keeping up with the pace of Moore’s law has proven to be extremely difficult. Now, many tech-based industries find themselves in a vulnerable position, wondering how far we can push technology.

Better materials, better chips

In an effort to continue Moore’s law and produce the next generation of electronic devices, researchers have begun looking to new materials and potentially even new designs to create smaller, cheaper, and faster chips.

“People keep saying of other semiconductors, ‘This will be the material for the next generation of devices,’” says Fan Ren, professor at the University of Florida and technical editor of the ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology. “However, it hasn’t really changed. Silicon is still dominating.”

Silicon has facilitated the growth predicted by Moore’s law for the past decades, but it is now becoming much more difficult to continue that path.

In the past, researchers looked to gallium arsenide-based devices to provide the next generation of high speed circuits, such as the aluminum gallium arsenide-based high electron mobility transistor (HEMT) invented at Bell Labs. However, gallium arsenide based devices have only become standard in some important niche applications.

Now, in a more modern attempt to move away from silicon to the next big material, researchers have started looking at materials such as 2D black phosphorus or metal dichalcogenides and graphene to continue electronic growth. For Ren, the temporary roadblock is not so much a downfall as it is a challenge.

“That’s part of the fun,” Ren says. “Everyone is competing with each other to find the next big thing.”

Progress predicted by Moore’s law

Recently, The New York Times published an article examining how Moore’s law has helped guide the tech industry to where it is today and what could happen if the law becomes obsolete.

This from The New York Times:

When Moore made his observation, the densest memory chips stored only about 1,000 bits of information. Today’s densest memory chips have roughly 20 billion transistors. To put it another way, the iPad 2, which went on the market in 2011 for $400 and fits in your lap, had more computing power than the world’s most powerful supercomputer in the 1980s, a device called the Cray 2 that was about the size of an industrial washing machine and would cost more than $15 million today.

The progress in semiconducting devices since Moore’s prediction has been monumental. Lili Deligianni, senior researcher at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center, is one of the scientists who helped make our electronics smaller, faster, and cheaper. For her, the answer to building better electronics was also in design materials.

“A chip has a transistor, which is the brain, and on top of that there are 12 metal levels that bring the current out to the world,” Deligianni, ECS secretary, says. “So the brain has to connect to the outside world and that’s done through the chip wiring.”

Deligianni and her team decided to speed this process up by replacing the traditionally used aluminum wiring material with copper, which is twice as conductive.

“That was really a breakthrough and it created much faster chip technology for the world,” Deligianni says.

Vulnerability of an industry

While some see the current state of chip research and development as the death of Moore’s law, others note it as nothing more than a blip on the radar.

“I have witnessed the advertised death of Moore’s Law no less than four times,” Brian Krzanich, Intel’s chief executive, wrote in a statement on the company’s website last month.

With many businesses being built on the principals of Moore’s law (i.e. Google and Apple), there is much concern in Silicon Valley as to what the future holds for the semiconducting industry.