Scientists have learned how to tame the unruly electrons in graphene.

Scientists have learned how to tame the unruly electrons in graphene.

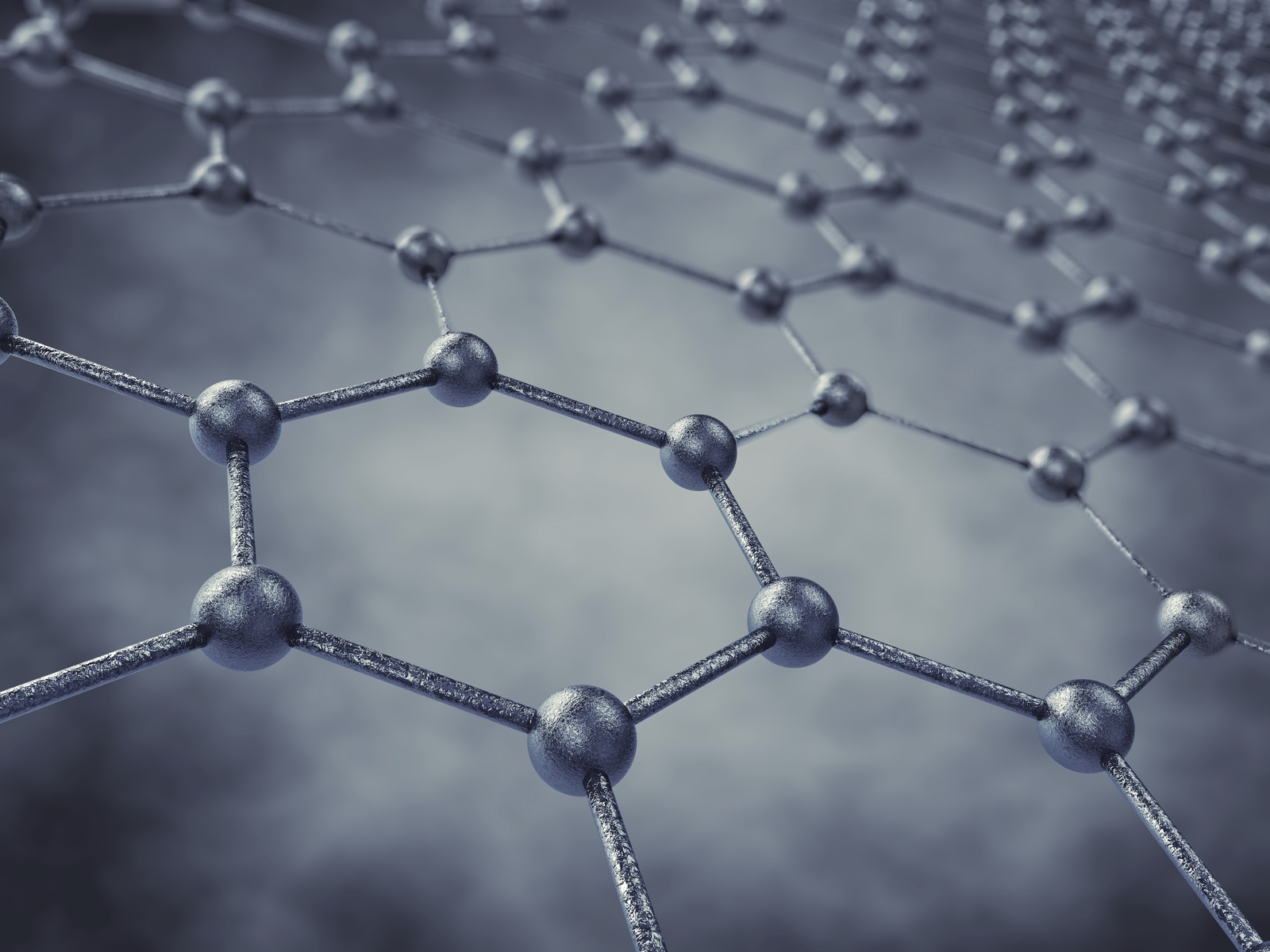

Graphene is a nano-thin layer of the carbon-based graphite in pencils. It is far stronger than steel and a great conductor. But when electrons move through it, they do so in straight lines and their high velocity does not change. “If they hit a barrier, they can’t turn back, so they have to go through it,” says Eva Y. Andrei, professor in the Rutgers University-New Brunswick department of physics and astronomy and the study’s senior author.

“People have been looking at how to control or tame these electrons.”

Graphene is a better conductor than copper and is very promising for electronic devices.

The new research “shows we can electrically control the electrons in graphene,” says Andrei. “In the past, we couldn’t do it. This is the reason people thought that one could not make devices like transistors that require switching with graphene, because their electrons run wild.”

Now it may become possible to realize a graphene nano-scale transistor, Andrei says. Thus far, graphene electronics components include ultrafast amplifiers, supercapacitors, and ultralow resistivity wires. The addition of a graphene transistor would be an important step towards an all-graphene electronics platform.

Other graphene-based applications include ultrasensitive chemical and biological sensors, filters for desalination, and water purification. Graphene is also under development in flat flexible screens, and paintable and printable electronic circuits.

Her team managed to tame these wild electrons by sending voltage through a high-tech microscope with an extremely sharp tip, also the size of one atom. They created what resembles an optical system by sending voltage through a scanning tunneling microscope, which offers 3D views of surfaces at the atomic scale.

The microscope’s sharp tip creates a force field that traps electrons in graphene or modifies their trajectories, similar to the effect a lens has on light rays. Electrons can easily be trapped and released, providing an efficient on-off switching mechanism, according to Andrei.

“You can trap electrons without making holes in the graphene,” she says. “If you change the voltage, you can release the electrons. So you can catch them and let them go at will.”

The next step would be to scale up by putting extremely thin wires, called nanowires, on top of graphene and controlling the electrons with voltages, she says.

Their study appears in Nature Nanotechnology. The study’s co-lead authors are from Rutgers and Universiteit Antwerpen in Belgium.

This article appeared on Futurity. Read the full article.

Source: Rutgers University

Original Study DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2017.181