Scientists have turned wood into an electrical conductor by making its surface graphene.

Scientists have turned wood into an electrical conductor by making its surface graphene.

Chemist James Tour of Rice University and his colleagues used a laser to blacken a thin film pattern onto a block of pine. The pattern is laser-induced graphene (LIG), a form of the atom-thin carbon material discovered at Rice in 2014.

“It’s a union of the archaic with the newest nanomaterial into a single composite structure,” Tour says.

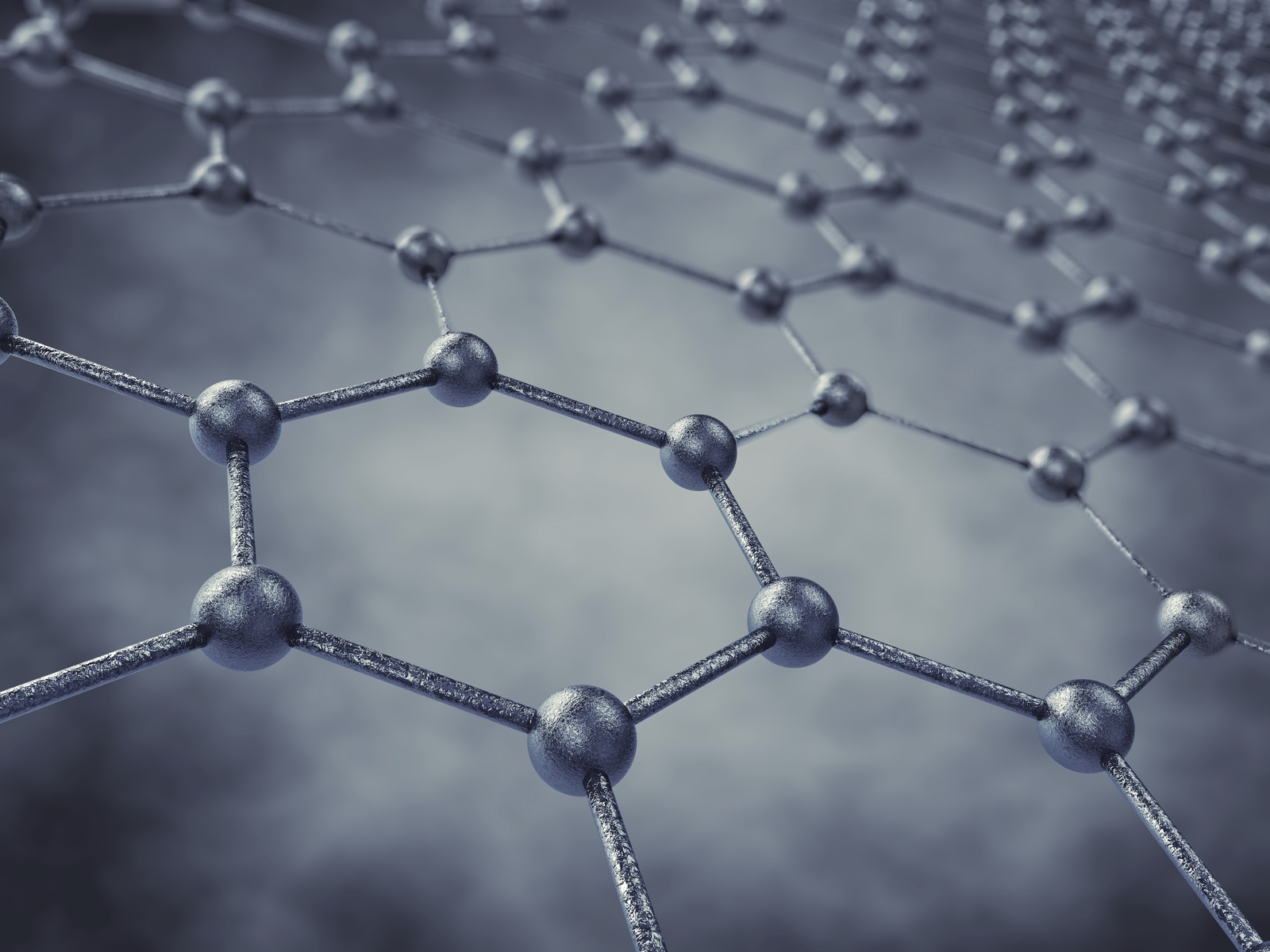

Previous iterations of LIG were made by heating the surface of a sheet of polyimide, an inexpensive plastic, with a laser. Rather than a flat sheet of hexagonal carbon atoms, LIG is a foam of graphene sheets with one edge attached to the underlying surface and chemically active edges exposed to the air.

Not just any polyimide would produce LIG, and some woods work better than others, Tour says. The research team tried birch and oak, but found that pine’s cross-linked lignocellulose structure made it better for the production of high-quality graphene than woods with a lower lignin content. Lignin is the complex organic polymer that forms rigid cell walls in wood.

Turning wood into graphene opens new avenues for the synthesis of LIG from nonpolyimide materials, says Ruquan Ye, who led the research team with fellow graduate student Yieu Chyan. “For some applications, such as three-dimensional graphene printing, polyimide may not be an ideal substrate,” Ye says. “In addition, wood is abundant and renewable.”

As with polyimide, the process takes place with a standard industrial laser at room temperature and pressure and in an inert argon or hydrogen atmosphere. Without oxygen, heat from the laser doesn’t burn the pine but transforms the surface into wrinkled flakes of graphene foam bound to the wood surface. Changing the laser power also changed the chemical composition and thermal stability of the resulting LIG. At 70 percent power, the laser produced the highest quality of what they dubbed “P-LIG,” where the P stands for “pine.”

The lab took its discovery a step further by turning P-LIG into electrodes for splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen and supercapacitors for energy storage. For the former, they deposited layers of cobalt and phosphorus or nickel and iron onto P-LIG to make a pair of electrocatalysts with high surface areas that proved to be durable and effective.

Depositing polyaniline onto P-LIG turned it into an energy-storing supercapacitor that had usable performance metrics, Tour says.

“There are more applications to explore,” Ye says. “For example, we could use P-LIG in the integration of solar energy for photosynthesis. We believe this discovery will inspire scientists to think about how we could engineer the natural resources that surround us into better-functioning materials.”

Tour saw a more immediate environmental benefit from biodegradable electronics.

“Graphene is a thin sheet of a naturally occurring mineral, graphite, so we would be sending it back to the ground from which it came along with the wood platform instead of to a landfill full of electronics parts.”

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative and the NSF Nanosystems Engineering Research Center for Nanotechnology-Enabled Water Treatment supported the research.

This article originally appeared on Futurity. Read the full article.

Source: Rice University

Original Study DOI: 10.1002/adma.201702211